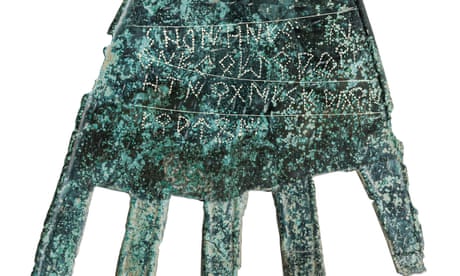

More than 2,000 years after it was probably hung from the door of a mud-brick house in northern Spain to bring luck, a flat, lifesize bronze hand engraved with dozens of strange symbols could help scholars trace the development of one of the world’s most mysterious languages.

Although the piece – known as the Hand of Irulegi – was discovered last year by archaeologists from the Aranzadi Science Society who have been digging near the city of Pamplona since 2017, its importance has only recently become clear.

Experts studying the hand and its inscriptions now believe it is both the oldest written example of Proto-Basque and a find that “upends” much of what was previously known about the Vascones, a late iron age tribe who inhabited the area before the arrival of the Romans, and from whose ancient language modern-day Basque, or euskera, is thought to descend.

Until now, scholars had understood that the Vascones had no written language – save for words found on coins – and only began writing after the Romans introduced the Latin alphabet. But the five words written in 40 characters identified as Vasconic, suggest otherwise.

The first – and only word – to be identified so far is sorioneku, a forerunner of the modern Basque word zorioneko, meaning good luck or good omen.

“This is the first document undoubtedly written in the Vasconic language and in characters that are also Vasconic,” said Javier Velaza, a professor of Latin philology at the University of Barcelona and one of the experts who deciphered the hand.

“The writing system used is odd – it’s a writing system derived from the Iberian system, although there have been some adaptations to represent some sounds and phonemes that don’t exist in Iberian characters, but which have been seen in coins minted in Vascones territory.”

As a result, added Velaza, the Hand of Irulegi proves the existence of a specifically Vasconic writing system in use at the time it was made.

His colleague Joaquín Gorrochategui, a professor of Indo-European Linguistics at the University of the Basque Country, said the hand’s secrets would change the way scholars looked at the Vascones.

“This piece upends how we’d thought about the Vascones and writing until now,” he said. “We were almost convinced that the ancient Vascones were illiterate and didn’t use writing except when it came to minting coins.”

According to Mattin Aiestaran, the director of the Irulegi dig, the site owes its survival to the fact that the original village was burned and then abandoned during the Sertorian war between two rival Roman factions in the 1st century BC. The objects they left behind were buried in the ruins of their mud-brick houses.

“That’s a bit of luck for archeologists and it means we have a snapshot of the moment of the attack,” said Aiestaran. “That means we’ve been able to recover a lot of day-to-day material from people’s everyday lives. It’s an exceptional situation and one that has allowed us to find an exceptional piece.”

Not every recent Basque language discovery, however, has lived up to its billing. Two years ago, a Spanish archaeologist was found guilty of faking finds that included pieces of third-century pottery engraved with one of the first depictions of the crucified Christ, Egyptian hieroglyphics, and Basque words that predated the earliest known written examples of the language by 600 years.

Although the archaeologist, Eliseo Gil, claimed the pieces would “rewrite the history books”, an expert committee examined them and found traces of modern glue as well as references to the 17th-century French philosopher René Descartes.